Zimbabwe election: what the strongman left behind

With millions of voters desperate for a functioning economy, Robert Mugabe’s successor in the ruling party faces a tough fight to retain power

The overnight train from Harare, Zimbabwe’s capital, to Bulawayo, the southern African nation’s second city, has not just seen better days. It has seen better decades.

Its gutted fittings — filthy seats, broken windows, carriages in pitched darkness — and decrepit rolling stock are a potent symbol of the destitution left behind by Robert Mugabe, the post-independence strongman toppled in a military coup last year. He was replaced as president and leader of the ruling Zanu-PF party by an estranged henchman, Emmerson Mnangagwa, who now proclaims one of the world’s most isolated economies “open for business”.

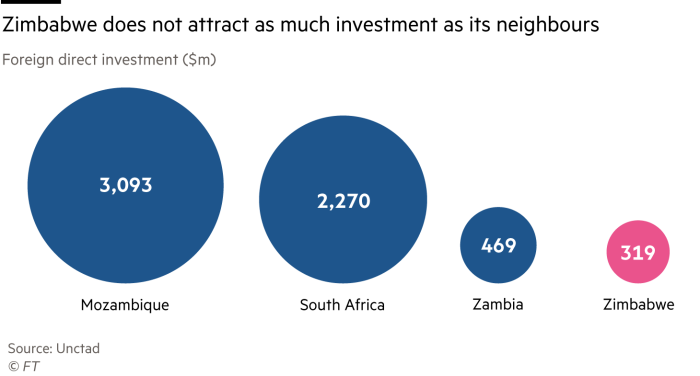

Mr Mugabe, 94, spends his days between Singaporean hospitals and a gilded-cage Harare mansion. But as Zimbabwe holds its first ever election without him on the ballot on Monday, a critical vote for convincing foreign investors to return, his legacy has yet to be exorcised — including from the rails.

The Harare to Bulawayo service should be the economic backbone of Zimbabwe as it straddles agricultural heartlands and the world’s second biggest platinum reserves. Instead, says Wisdom Khawo, a passenger wrapped in a thick coat and barely visible in the dark, “it’s like travelling in hell”.

One of a forlorn few who still brave the service the 39-year-old former truck driver turned fish seller endures it 10 times a month back and forth. The $5 fare is all he can afford. The bus costs five times the price, but is reduced to $20 if paying in US dollars instead of surrogate money — officially worth the same but worth much less in practice — used to meet a desperate shortage of the real thing.

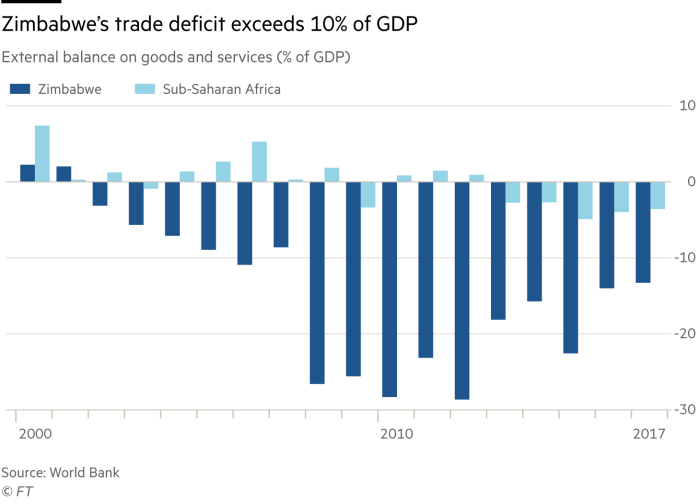

Mr Khawo is a victim of an economy that has been brought to its knees. The economy is $17bn in size but real output is still below 1998 levels, in a country without a currency since hyperinflation 10 years ago. The next time he takes the train, it will be to cast a vote on who will lead Zimbabwe’s difficult transition.

Mr Mnangagwa, a 75-year-old former security chief one of whose vice-presidents was the coup mastermind, says his once Marxist-leaning liberation movement will restore stable rule to attract international investors and even encourage the return of white farmers who fled after Zanu-PF seized their land in the 2000s.

His main rival is Nelson Chamisa, a charismatic 40-year-old lawyer and pastor, who inherited the main opposition Movement for Democratic Change after Morgan Tsvangirai, Mr Mugabe’s old foe, died earlier this year.

He promises Zimbabwe will be a $100bn economy in a decade and touts eye-catching policies at odds with grim reality — including a bullet train to cover the 440km distance between Bulawayo and Harare in less than an hour. State media outlets enjoy mocking it, but while the concept is outlandish Mr Chamisa “understands very well how we are suffering”, Mr Khawo says. “We need to refurbish our country.”

In a world where strongman politics is on the march, Zimbabwe shows what strongmen leave behind. Under Mr Mugabe, Zanu-PF displayed a fondness for rigging elections. This time, with an eye on its shaky post-coup legitimacy, the party is protesting its commitment to democracy almost too much.

State media says Mr Mnangagwa, who has invited international election observers banished under his predecessor, “has made the democratic space as expansive as the ocean”. His catchphrase, emblazoned on giant billboards, states that “the voice of the people is the voice of God”.

The overt violence that turned elections in Mr Mugabe’s favour is absent, and even in Zanu-PF’s heartlands Mr Chamisa has held rallies without being harassed. Diplomats hope a biometric voter registration system will stop blatant ballot-stuffing.

But God may still get a helping hand. When the election commission unveiled the ballot paper design, Mr Mnangagwa appeared top despite being 15th in the list, thanks to serendipitous separation of the 23 candidates into two columns.

Zanu-PF’s will to stay in power has shaped Zimbabwe deeply. Last year, the country’s registrar-general denied that babies born in opposition strongholds, such as Bulawayo, were being refused birth certificates to prevent them registering to vote as adults years later. On Tuesday, the UN human rights office warned of evidence of “voter intimidation . . . including people being forced to attend political rallies”. Yet this vote could be the closest for years.

A survey last week of 2,400 voters by Afrobarometer found 37 per cent backed Mr Chamisa, against 40 per cent for the incumbent whose party controls most media and access to state resources. A fifth were undeclared. Parliamentary polls are also tight. Afrobarometer warns of Zanu-PF’s “built-in electoral advantage” — its domination of rural areas, where two-thirds of Zimbabweans live. But its findings imply that a second round in the presidential race, in September, could take place.

Zanu-PF reacted to a runoff in 2008 with violence against the opposition — resulting in international condemnation that forced Mr Mugabe into a brief unity government. A runoff next month “would be a true test of their mettle, whether they are prepared to play the democratic game,” says Piers Pigou, an International Crisis Group analyst.

Tempers have risen along Zimbabwe’s economic and generational divides. “Chamisa is a young ruler. That old man can get off,” says Tinashe Chiringa, a jobless 29-year-old in Harare convinced that Mr Mnangagwa can only win through rigging. “If Chamisa loses, we are ready for war, fighting against Zanu-PF,” he warns.

There are other signs of instability, within both main parties. There will be two MDCs on the ballot paper, due to infighting triggered by Mr Chamisa’s rise. And Mr Mnangagwa narrowly escaped a June 23 bomb attack at a campaign rally in Bulawayo. He blamed it on his “usual enemies”, code for factions in his own party. He has a long-running rivalry with Mr Mugabe’s wife, Grace. There is another element: the generals who have already displayed their will to intervene in politics.

Few believe that the coup plotters risked their lives last year to rescue the ruling party only for it to lose in a democratic vote months later. Nearly half of those polled by Afrobarometer believe the security forces would annul a result they do not like.

“You don’t take power to give away power,” says Panashe Chigumadzi, a Zimbabwean-born writer who fears the future may indeed bring a “western-backed, military-backed order that we will find very difficult to get out of”, resembling Paul Kagame’s Rwanda.

Yet Ms Chigumadzi sees a chance to reimagine Zimbabwe’s patriarchal politics and history with the freedoms of expression and a sense of possibility that have taken root since the coup.

“[For years] we haven’t been able to see beyond the shadow of Mugabe,” she says, “now that he’s gone, people are free to imagine not just what they’re against, but what they’re for.”

That freedom is manifesting itself in unusual places. Among the thousands who followed the tanks on to the streets to demand Mr Mugabe’s downfall in November was Chester Samba. He is a gay man — a member of a community vilified by Zanu-PF under Mr Mugabe, who called homosexuality a “filthy, filthy disease”. Although Mr Samba is the director of Gays and Lesbians of Zimbabwe, southern Africa’s oldest LGBTI rights group, he had never dared protest before.

“It was a first for me to go on the streets, to express my feelings, my rage against Robert Mugabe, Zimbabwe’s most vocal homophobe,” Mr Samba says. “I’d never had that opportunity to express myself.”

He wondered whether the opportunity would last. When he wrote to the main parties about their LGBTI policies ahead of the election — he had a shock. Zanu-PF not only replied, the sole party to do so, it also invited his group to its headquarters. “They told us we have a new dispensation and we would like to do things differently,” Mr Samba says. He sees the shift as a sign that Zanu-PF is going all-out to win back legitimacy. Still, “we want to see how they behave when they have that legitimate power”.

For some there is no going back — including many among the over 4,000 white farmers who were subject to land seizures under Mr Mugabe and now hear the promises from Mr Mnangagwa.

Daniel, a white former farmer, endured “18 years of hell” before Zanu-PF finally seized his 2,000 hectares of land in 2012. “I made a cat look silly, I had more than nine lives,” he says, declining to use his real name as the memories of intimidation are still fresh.

He still has the title deeds. But he does not expect to ever return home. Mr Mnangagwa may “compensate in a way that is going to put agriculture back on its feet”, such as reviving overall investment, but the political moment to restore individual farms is gone, he says.

Recommended

Scarcely mentioned in the election excitement is that Zimbabwe’s immediate economic future is likely to mean difficult structural adjustment — the price of the $2bn in arrears to the World Bank and other lenders built up during the Mugabe-era, and which must be cleared before new loans can begin.

The country is also likely to need debt relief and a long-term solution to lacking a currency of its own ever since the Zimbabwe dollar was destroyed by hyperinflation 10 years ago. “We’re watching — everybody’s watching. But there are complicated issues that must be resolved first,” says a Chinese banker.

Breathless early comparisons of Mr Mnangagwa with authoritarian reformers, a Zimbabwean Deng Xiaoping or Mikhail Gorbachev, have fallen silent.

In Ethiopia, a similar glasnost moment this year brought sweeping economic reforms, a thaw in the bitter cold war with Eritrea and a young prime minister who acknowledged past oppression by security services.

By contrast, a big achievement Mr Mnangagwa cites for his rule so far is removing corrupt police roadblocks — which largely vanished during the coup. Traffic cops remain almost as rare as dollars. There has been little improvement in the shortage of cash, which is intimately linked to the issuing of electronic dollars that have no physical backing. The state has stuffed banks with dollar-denominated debt to finance spending. Bank deposits of $8bn far outweigh cash in the system.

Gresham’s law — that states bad money drives out good — has set in, as physical US dollars vanish into safe deposit boxes and under mattresses. Mr Chamisa has said the MDC would abolish the surrogate bond notes that have replaced them. But without a fallback currency, economists say a solution probably has to include a loan of at least $1bn to $2bn to build up reserves, and a painful devaluation of electronic dollars in banks by up to half.

It is a forbidding prospect. But as the vote nears, many Zimbabweans are reflecting on how far the country has already moved, and how far it has to go.

Mr Samba says: “I’m no longer worried about the car that’s parked on the street corner, if I’m being followed, who is listening in . . . it lifts a heavy load off you as an individual.

“The political balance is very delicate. But for now, I’m just enjoying this moment.”

‘Shaking the matchbox’ Old-style electoral rigging is still a factor in digital age

Zimbabwe’s first post-Mugabe vote has brought long-banished international election observers back to the country. But they will face a major test in spotting whether the ruling Zanu-PF party is abandoning a history of vote-rigging, or just moving it out of sight.

Stephen Chan helped invent modern African election monitoring in the 1980 vote that first installed Mr Mugabe in what was then Southern Rhodesia.

“What we did in 1980 is viewed as some kind of gospel,” says Mr Chan, then a Commonwealth official, now a professor at the University of London’s SOAS. “[But] we didn’t know what we were doing. We made it up. We got very lucky.”

The rudiments of election observation — monitors fanning out to watch polling stations across a country — have not changed much since. But governments have.

Aware that international observers can provide a veneer of legitimacy, regimes may invite several bodies to play them off against one another. Monitors from the Commonwealth and EU are among those operating in Zimbabwe alongside the African Union. Ruling parties have also moved in recent times from blatant ballot-stuffing to tampering with data servers.

In their recent book How to Rig an Election Nic Cheeseman and Brian Klaas warned that in light of the rise of digital manipulation, monitoring “has not really moved with the times”, adding that “few missions have the technical capacity they need”.

Africa is a frontline in that battle. Elections in Zambia in 2016 and Kenya last year showed signs of data manipulation that may have swung votes. Zimbabwe’s biometric voting is meant to prevent a repeat but “if this election is going to be fixed, it will be fixed in the algorithms,” Mr Chan says.

Yet even in the digital age, he says, observers need knowledge of the local culture and a willingness to go deeper into rural areas to pick up signs of subtle intimidation — called “shaking the matchbox” in Zimbabwe.

No comments:

Post a Comment