Uma coisa que me irrita na maneira como a crise política em Moçambique é analisada por muitos de nós é o que chamo de „infantilização” da Renamo. Este fenómeno consiste na tendência de abordar a crise como consequência do que o governo fez ou não fez. À Renamo não é reservado outro papel senão o de vítima que, tal como uma criança, pode reagir como quiser sem temer nenhuma responsabilidade pelos seus actos porque, prontos, é como uma criança e crianças não sabem o que fazem. Este fenómeno conduz a um revisionismo problemático que procura reinterpretar a história de forma que ela explique o que acontece hoje, mesmo quando é impossível estabelecer relações plausíveis entre o passado e o presente. Este revisionismo manifesta-se no constante e, entretanto, irritante recurso que se faz ao Acordo Geral de Paz para explicar porque a Renamo continuou armada, não tem palavra, considera-se acima da lei e como poder paralelo. Fazendo justiça à tese de infantilização, muitos dos que se entregam a este revisionismo raramente se dão ao trabalho de olhar para a evolução da Renamo desde o fim da guerra dos 16 anos e o que ela fez de si como força política. O autoritarismo do seu líder e ausência de democracia interna na Renamo nunca é tema. Inversamente, a forma como a Frelimo se renova e segue os trâmites democráticos para a renovação das suas estruturas não tem absolutamente nenhum peso na avaliação das suas credenciais democráticas. O defensor da democracia no nosso país é aquele que não a pratica.

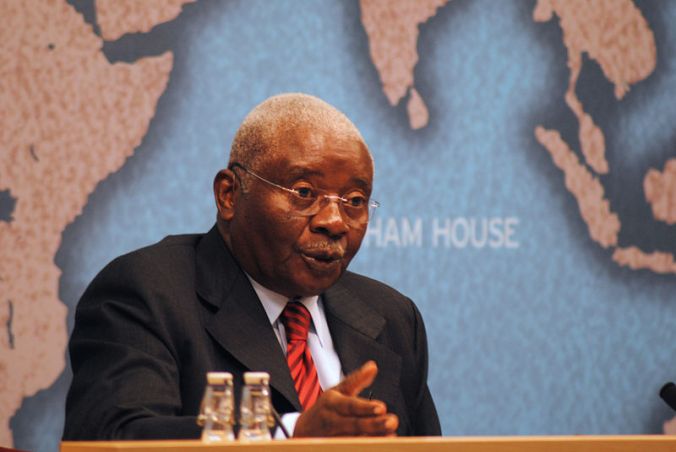

Carrie Manning, uma cientista política americana, fez uma das análises mais interessantes sobre a evolução da Renamo no período pós-Roma que devia ser de leitura obrigatória para todos aqueles que se entregam ao revisionismo histórico. Essa análise está contida numa obra de 2008 com o título “The Making of Democrats: Elections and Party Development in Postwar Bosnia, El Salvador, and Mozambique, New York: Palgrave Macmillan.”. Como sei que muita gente na Pérola do Índico observa altos critérios de imparcialidade para se deixar convencer por argumentos com sentido deixo aqui uma análise recente dela do conflito moçambicano (não se assustem com a foto do Guebas, o artigo tem também uma foto do grande líder das massas) onde ela revela compreensão, sem ser parcial, em relação à Renamo. Depois de lerem este texto procurem pelo livro mencionado a ver se algumas mentes se abrem.

O grande problema na Pérola do Índico não são necessariamente os políticos. É uma massa “intelectual” que apenas aposta na proteção das suas próprias crenças. Este problema é tanto maior quanto maior for a hostilidade em relação ao partido que está no poder. Há gente que acredita que só merece o estatuto de intelectual se for “neutra”. E ser “neutro” entre nós significa considerar errado tudo o que o governo da Frelimo faz ao mesmo tempo que se infantiliza a Renamo. Daí que seja fácil rejeitar um argumento visto como estando a defender o lado governamental das coisas. Há um instinto “Polícia de choque anti-G40” que é activado assim que alguém se apercebe que um argumento esteja a pender perigosamente para a versão governamental das coisas. E deixa de pensar. De repente a “neutralidade” é convocada para arbitrar o raciocínio como se ela alguma vez tivesse sido importante para uma postura intelectual honesta e íntegra. É claro que nunca foi. A “objectividade”, essa sim, e é possível independentemente das preferências políticas de quem se entrega ao trabalho académico. Não é a “neutralidade” que torna possível o debate de ideias na esfera pública, mas sim a “objectividade” que quando garantida até pode permitir que se chamem as coisas pelos seus nomes. Uma dessas coisas é que a atitude da Renamo tem sido uma afronta a todo o sentido de democracia.

Peacemaking and Democracy in Mozambique: Lessons Learned, 1992-2014

By Carrie Manning

For the past quarter-century, sub-Saharan Africa has been an arena of political, economic, and social transitions. Different trajectories have been pursued in its 49 states. The reflections of a new generation of Africa scholars, who have built their careers tracing these developments, will increasingly be featured in AfricaPlus.[1] Carrie Manning is a member of this cohort of scholars who possess a deep understanding of the dynamics in play, great knowledge of the political actors, and are fully aware of the pertinent theoretical issues.

Mozambique represents a striking model of peace building and democracy. Armed struggle against Portuguese rule was succeeded by a civil war fanned by the South African apartheid regime. Externally-facilitated peace talks resulted in two decades of imperfect democratization. These experiences, in which the losing party in the civil war, the Mozambique National Resistance (Renamo), has been a subordinate participant in state and democratic institutions, contrasts with that of Angola where the armed opposition, The National Union for the Total Independence of Angola (UNITA), was forcefully eliminated. In view of its ever-growing resource wealth, vast land acreage, a liberalized economy, and fitful democracy-, peace-, and state-building, the evolution of Mozambique merits close attention. It shows how post-conflict electoral politics has been complemented by consociational norms of consultation, compromise, and inclusion. The recent slaying of a prominent lawyer echoessimilar incidents in Botswana where the struggle for political power is also exacerbated by natural resource wealth and the plentiful spoils of economic growth.

Since the end of the Cold War in 1990, “liberal peacebuilding” has dominated post-conflict politics. Liberal peacebuilding privileges electoral politics in the negotiation of political agreements. There has been much debate over the effectiveness of this approach in generating peace and democracy. In most cases in which civil wars ended in 1990 or later, provisions were made for the conversion of armed opposition groups into political parties. They participated in the founding elections and continue to do so. Moreover, they have performed relatively well, gaining representation in the national legislature about a quarter of the time, and averaging around 20% of the legislative seats.[2]

To point to the consistency and longevity of post-conflict institutional arrangements is not to say that there are many democratic success stories. It does suggest, however, that ex-belligerents have often adapted themselves to regular, periodic electoral contests. While the democratic results have varied, norms and patterns of electoral politics, though falling short of liberal democracy, have nonetheless influenced the expectations of political actors. They have also shaped citizens’ evaluations of state legitimacy even in cases when conflict resumed.

The Peace-Conflict Cycle

The case of Mozambique, where armed conflict resumed after more than twenty years of peace, demonstrates this point. The resumption of armed conflict in 2013-14, and the way it was resolved, suggest that the original peace settlement – and its initial reinforcement by outside actors – has influenced the expectations of opposition elites and citizens regarding the legitimacy of the political settlements. Indeed, these expectations played a powerful role in the system’s survival, and in ending the renewed conflict. These expectations center on regular electoral competition that is transparent and accompanied by civil liberties.

Mozambique was an early success story for liberal peacebuilding. In October 1992, a negotiated peace agreement ended sixteen years of civil war. The implementation of this agreement was overseen by a U.N. Observer Mission, UNOMOZ, in conjunction with the country’s major donors. The first multiparty elections in October 1994 marked the end of the formal transition process. Two decades of peace and four consecutive general and municipal elections followed. During this period, even peaceful demonstrations were unusual and violent ones rare. The former armed opposition group, Renamo, has participated in every presidential and legislative election and most municipal contests.

In April 2013, however, violent conflict erupted between Renamo and the government. An agreement in September 2014 following negotiations enabled the fifth general elections to take place the following month. New natural resource discoveries, changes in inter-party political dynamics, incomplete enactment of parts of the peace agreement, and Renamo’s enduring organizational weaknesses all contributed to this outcome. But what is evident from the ending of this conflict was how deeply the norms of political interaction had become established during the first peacebuilding phase.

Mozambique’s peace implementation process had the usual challenges deriving from mutual mistrust and differing interpretations of provisions of the accord, but these were resolved because of consistent attention by international actors. These included differences over the employment of Renamo’s civilian personnel in state administration in rebel-held zones, and the composition of the National Election Commission (CNE).[3] These and other issues, like security sector reform and the integration of the bodyguard of Renamo’s leader, Afonso Dhlakama, and other security forces into the police, occasionally prompted recriminations or demands for renewed negotiations. Generally speaking, both sides were satisfied enough to avoid resorting to violence to alter the settlement. Perhaps most important, donors were willing to fund and monitor the first election and, to a lesser extent, subsequent elections. International actors therefore served as effective guarantors of the transition to electoral politics.

Though both major political parties embraced electoral politics, they were reluctant to have their fate depend entirely on the outcome of elections. From the beginning, Renamo saw participation in elections as necessary but not sufficient political instruments. It expected elections to be supplemented by consultation and negotiation between the two major parties because it perceived the state as lacking the credibility to act as both contestant and referee.

The Front for the Liberation of Mozambique (Frelimo) for its part asserted its preference for elections to determine the allocation of power, but it repeatedly rebuffed criticisms of the lack of transparency and unfairness. In other words, acceptance of electoral politics by the ruling party was based on the expectation that it would control voting processes and limit transparency and oversight. Over time, both sides fell into a pattern in which elections resulted in opposition protests. These were often followed by face-saving consultations between the party leadership, which often did not produce changes in procedures or outcomes. These exercises sufficed, however, for restoring peace. During the first post-conflict decade, though Frelimo always emerged as the victor, Renamo made a credible showing in the popular vote. This pattern, together with post-election consultations, kept the opposition party from feeling entirely marginalized – at least for a while.

Presidential election results, 1994-2014

| Presidential elections | 1994 | 1999 | 2004 | 2009 | 2014 |

| Frelimo | 53.3 % | 52.3% | 63.7% | 75.0% | 57.0% |

| Renamo | 33.7 | 47.7 | 31.7 | 16.4 | 36.6 |

| Other Parties | 13.0 | 0 | 4.6 | 8.6 (MDM) | 6.36 (MDM) |

Parliamentary election results, 1994-2014

| Legislative elections | 1994 | 1999 | 2004 | 2009 | 2014 |

| Frelimo | 129 seats | 133 seats | 160 seats | 191 seats | 144 seats |

| Renamo | 112 | 117 | 90 | 51 | 89 |

| Other parties | 9 | 0 | 0 | 8 (MDM) | 17 (MDM) |

Party Dynamics and Renewed Conflict

After Frelimo’s candidate, Armando Emilio Guebuza, was elected President in 2004, interparty dynamics began to change. A trend toward increasingly lopsided electoral wins by Frelimo was accompanied by the abandonment by Frelimo’s leadership of any pretense of consultation or consensus-building with the opposition.

In 2008, a new party, the Democratic Movement of Mozambique (MDM), was formed following a dispute within Renamo. MDM attracted a significant share of Renamo’s mid-level party leadership, including some of its parliamentary bench. MDM’s leader and presidential candidate, Daviz Simango, performed well enough in the 2009 elections to alarm both major parties. This development, plus the ever-increasing opportunities for rent-seeking from natural resource discoveries, prompted Renamo and Frelimo to revisit the terms of the post-war settlement. Renamo sought to turn back the clock, reassert its role as the government’s “partner in peace”, and claim its share of national resources. This demand became doubly important as other sources of Renamo’s income, such as a state financial allowance based on seats in the legislature, were shrinking.

In April 2013, Renamo threatened to disrupt commercial road and rail traffic to protest the failure of protracted negotiations with the government over, most importantly, security sector reform and election administration. The violence was reminiscent of the 1977-92 war with Renamo attacking police stations and firing on civilian road traffic. By June, Renamo had returned to the bush in central Mozambique and declared the 1992 Rome peace accord defunct.

Feeling less constrained by foreign donors and more confident of its electoral prowess, Frelimo initially responded with force. In the wake of new-found natural resources, and with the prospect of more demands, the ruling party had stronger incentives to reject a return to the parity and consensus that characterized the aftermath of peace negotiations. Bellicose rhetoric escalated and lethal attacks were conducted by both sides. The violence persisted for another year.

At the same time, both sides continued to negotiate, this time without the formal involvement of mediators whether foreign or domestic.[4] Negotiations to end the second conflict included demands that certain unmet commitments for opposition inclusion – from as far back as the 1992 peace accord – be honored. The most important of these related to the integration of Renamo’s paramilitary members into the national police and security force, and a return to the election administration that involved greater oversight. Also included were new demands from Renamo for a larger share of the now expanding national wealth.

In February, the government agreed to amend the law on election administration to return to an administrative structure that involved more balanced representation of government and Renamo representatives. In September 2014, Dhlakama emerged from the bush – escorted to the capital, Maputo, by several Western ambassadors — and announced that his party would participate in the country’s fifth general elections the following month.

After the vote, Dhlakama and his party dismissed the elections as fraudulent and announced their intention to boycott the national legislature and provincial assemblies. Dhlakama threatened to divide the country and create a shadow government in the central and northern provinces. This was a familiar refrain — the same rhetoric Renamo deployed after nearly every election since 1994. This time, Frelimo also returned to its established pattern, which had been briefly interrupted by President Guebuza’s less tolerant attitude towards political opposition. The newly-elected President of the Republic, Filipe Nyusi (Frelimo), agreed to discuss Renamo’s demands and, on the surface at least, he has been more accommodating than Guebuza. In response to Dhlakama’s demand for autonomous provinces, he invited the opposition leader to submit a bill to parliament, while making no commitment that such a bill would get past the Frelimo majority. Moreover, while Guebuza is no longer president, he remains head of the ruling party and thus retains considerable influence.

In the end, Frelimo’s internal dynamics – and how they shape its responses to events – will likely be decisive for the country’s democratic future. As the only party ever to govern independent Mozambique, it has the most to lose. Political inclusion now means losing control over the natural resource boom and the spoils of the country’s strong postwar economic growth.

Not everyone sees political inclusion as a desirable goal. On March 3, 2015, gunmen murdered prominent constitutional lawyer Gilles Cistac on a crowded street during morning rush hour in the capital, Maputo. Cistac had recently stated that Renamo’s demands for provincial autonomy did not necessarily contravene Mozambique’s constitution. In response, he received explicit threats on social media. Cistac’s killers remain at large and all parties have condemned his slaying. His death serves as a reminder that, in spite of the ending of the most recent outbreak of armed conflict, “strategic violence” remains part of the political equation in Mozambique.[5]

The bright thread running through the country’s politics is mineral wealth. It helps explain both the return to armed conflict as well as the ending of that conflict. Reuters reported that, the week after the October 2014 election, 15 new onshore sites for gas and oil exploration were opened. It also underscores the high stakes of Renamo’s demands for autonomous provinces. Production has only just begun in some of the world’s most significant untapped reserves of natural gas and coal. Analysts believe coal and natural gas could double the country’s per capita wealth.[6] Much of the natural resource wealth is in the center and north, areas of strong political support for Renamo.

Voters to Citizens?

What makes these events more than just a story about inter-elite negotiation is that, even though Renamo initiated the resumed conflict in 2013, polls, newspaper accounts, and the election results show that the public did not assign all or even most of the blame for renewed conflict to it. Instead, many voices were raised during the second conflict episode – from independent media sources to respected academics and longtime ruling party supporters – castigating the government for failing to honor the post-conflict norms of inclusion and compromise. Moreover, the 2015 election results showed that voters did not hold Renamo alone responsible for renewed violence. Dhlakama’s vote share surpassed immediate postwar levels and more than doubled in the most recent election, though falling short of its high point in 1999 of 48%. The party won 89 seats in the national legislature in 2014, up from 51 in 2009. And the upstart party, MDM, won 6% of the presidential vote in 2014 and 17 seats in the legislature.

These results provide evidence that citizens’ notions of state legitimacy have begun to include the norms of political inclusion on which Renamo has historically insisted. And the government’s response – to return to a model of elections plus consultation and bargaining – suggests that it too acknowledged these same expectations about how politics should be conducted.[7]

Lessons Learned

To what extent does the Mozambique experience demonstrate the influence of liberal peacebuilding? The return to violence was clearly part of a strategic bargaining process in which Renamo sought to reprise its role as a military force. In so doing, it hoped to regain political relevance and restore the pattern of politics that had served the party well. Significantly in 1992 and 2014, Renamo placed political and economic inclusion at the center of its demands. These demands reflect a tacit acceptance of democratic politics as the legitimate basis of the Mozambican state. In 2014, they also reflected dissatisfaction over the substantive outcome of democratic politics during the previous two decades.

MDM and important sectors of civil society further seek to reshape the terms of the peace settlement by getting a significant role for non-belligerents in the political arena. By arguing that all parties must accept democratic politics as the basis of the state, it is not being suggested here that they are committed democrats or that Mozambique is becoming a consolidated democracy. Instead a modest but important proposition is advanced: political inclusion along democratic lines has become a fundamental understanding of the major political parties in Mozambique.

The violence-assisted bargaining that Mozambicans experienced in 2013-14 did not seek to change the underlying principles of the 1992 peace settlement. Rather, they were revisited to have them reflect twenty years of political practice and successive economic windfalls. Renamo demanded the depoliticization of state institutions, – or perhaps equal political representation in those institutions – since the state has remained under the control of the ruling party. However weak Renamo’s commitment might be to the core values of democracy, Mozambique’s imperfect democratization has shaped its political demands and fostered wider social support for them.

Successive elections have produced in MDM a viable opposition party whose route to power lies in greater democracy. Media and civil society groups have become more independent and outspoken in their criticisms of government corruption and intolerance. Inter-party competition has also highlighted tensions within the ruling party and placed constraints on the autocratic prerogatives of its principal leader.

The introduction of electoral competition in 1994 changed the form of politics, but it has not yet succeeded in transforming the state, which remains the province of the ruling party. The experience of Mozambique suggests that, if democratic politics is to make a positive contribution to post-conflict state-building, it will have to go well beyond competition for power via elections to address contenders’ and citizens’ understanding of the state and its role vis-à-vis society. If democratic politics unfolds alongside a state that continues to serve partisans rather than citizens, efforts to build state capacity will only reinforce a logic of exclusion and constrict avenues for change by political means.

Dr. Carrie Manning is a professor and chair of the political science department at Georgia State University. Her work focuses on post-conflict peacebuilding and democratization with a particular focus on southern Africa, especially Mozambique and Angola.

| Renamo adia eleição de juízes para os Tribunais Supremo e de Recurso |

| Escrito por Redação em 19 Fevereiro 2016 |

Os deputados do maior partido de oposição no Parlamento inviabilizaram a eleição dos juízes para o Tribunal Supremo e os Tribunais de Recurso das cidades da Beira e Nampula.

Nesta quinta-feira(18) a eleição foi feita e depois anulada em virtude de os deputados da oposição não terem entendido os objectivos e as formas de eleição, de acordo com a presidente da Assembleia da República, Verónica Macamo.

Os juízes eleitos, segundo a lei, podem participar nas decisões sobre questões de facto, mas não de direito. Eles devem ter entre 30 e 70 anos, e possuir um diploma de ensino superior. Devem ser também pessoas de boa reputação e com folha criminal limpa.

Ao contrário da grande maioria das eleições em que a AR faz para entidades externas, a escolha de juízes eleitos não se divide segundo linhas partidárias. Nenhum dos candidatos foi indicado por um partido político.

A selecção é através de um concurso público promovido pelo próprio parlamento.

|

Sem comentários:

Enviar um comentário